It goes against the grain … but where I don’t believe that honesty is the best policy

‘I’m just going to ring my mother,’ you said.

‘But Dad,’ I responded, ‘Gran died a long time ago’.

You looked shocked and sad.

‘No,’ you said.

The next morning the conversation was a repeat of what had been said the day before.

You forgot as quickly as I responded, but it was obvious that although you had forgotten what was actually said, the accompanying worry and sadness remained.

I don’t know why it hadn’t dawned on me earlier how cruel my response was; my only excuses are that I hadn’t wanted to mislead and that I hadn’t been back with my parents long and was relatively new to the day-to-day realities of dementia.

By the second day, I had realised that I had to go along with whatever you said, Dad.

‘I’m just going to ring my mother,‘ you said, ‘but what’s her number?’

‘Try later,’ Dad, ‘I don’t think Gran’s there now’.

‘Oh, right,’ was your only response.

Then you forgot, and you only occasionally ask now.

And, I suppose I mention this as a precursor to a conversation I recently had with a social worker (Autumn 2023). In view of my Mum’s health and the realisation that I would now need to leave more often for work, we had realised that Dad would have to go into a home, and the realisation hurt.

So, I was already raw when discussing the situation. Strangely, it wasn’t talk of care homes that set me off, it was when she said:

‘How does your Dad feel about that?’

I could feel my stress levels rising.

‘I can’t phrase it like that to Dad,’ I said. ‘That would just be cruel. He no longer has the cognitive ability to understand. It would just cause him needless upset’.

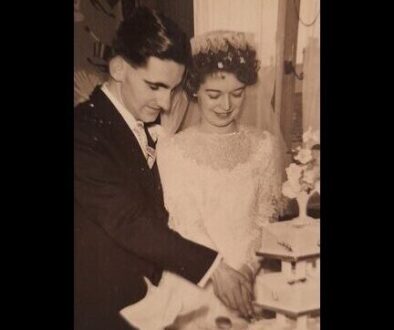

Already, I could imagine his hurt face looking at Mum and me, the worry in his eyes at our desertion of him, my Dad who loved my Mum, my sister and me above all else.

I felt distraught when I put down the phone.

In the beginning, I didn’t use support lines at all, but I had recently started to reach out to the Alzheimer Society’s dementia support line and that was my go-to now.

‘I can’t do it,’ I heard myself saying, ‘I can’t have an honest conversation with Dad; he just wouldn’t understand, and it would cause him so much pain, but I feel so bad about misleading him’.

It was such a relief when she reiterated what I already thought: that Dad would forget the conversation but probably be left with the feelings of sadness or worry that would accompany it. The conversation with her helped to allay the feelings of guilt, and it crystallised my approach.

That woman was a lifeline to me. She understood; she understood my guilt at lying but that honesty would be cruel where cognitive function didn’t exist anymore. There was no need to explain to her how upset I was about the thought of causing Dad severe distress should I tell him that he was going into care for good.

She said to me that if the next conversation upset me as much I should just ring again. Luckily, when I saw the social worker face-to-face and explained, she totally understood, but knowing that lifeline was there has made all the difference.