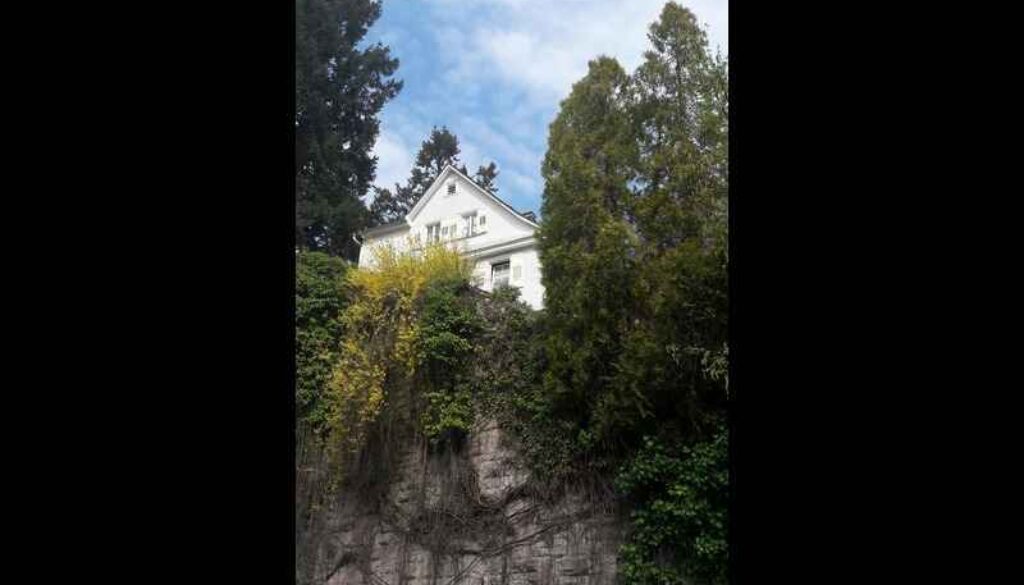

Brahms’ House Baden-Baden

Pausing momentarily, I looked up at the white house perched on the rock above me. I had only landed here because the Frieder Burda Museum was closed, it being a Monday. But already, before entering, I knew that this was where I was meant to be on that fine, still day in March in Baden-Baden, back in 2017.

I crossed the road and opened the gate, taking the steps up to the wooden building two at a time.

The notice outside the door read ‘please ring the bell’ so I did and, stepping back, waited. I could hear an echo somewhere inside and then footsteps on the stairs and the turning of a key.

A friendly woman opened the door to me.

‘Grüß Gott’, I said

She responded similarly, adding ‘Engländerin?’

It’s always apparent.

I followed her up the stairs into the little house.

She continued to speak to me in German, which I’ve always liked.

‘Do you know anything about Brahms?’ she asked.

I responded in the negative.

She told me that the house was Brahms’ summer home from 1865 to 1874, and that he spent time there to be near his dear friend, Clara Schumann.

Inside were a piano and work desk in one room, a bed in the other

The curator kindly opened the bedroom window for me, to get a better sense of what Brahms looked out over every morning.

There is a timeless quality about places like that, somehow imbued with the spirit of their former inhabitants. What had Brahms been thinking as he flung open the window and greeted a new day on those summer mornings? Was it frustration at a composition half-finished which wasn’t quite to his liking, or elation at a passage completed over which he had laboured long and hard? Was it something more than achievement: the delight of seeing a very dear friend again, plans already forming as to what the two of them would do that day?

I knew nothing of Brahms, nothing of Clara, nothing of classical music, but I was hooked. Their friendship was enough to entice me in.

So, I lingered there, soaking up the atmosphere, wondering, as dreamers do, about the lives of those two, marvelling at the magic of a morning meant originally for other things.

And the special feeling

associated with my trip

never went away. I returned

home with a poster of Brahms

in his youth, given to me

because it had been produced

to advertise his concerts and wasn’t

for sale.

On discovering more about how Johannes Brahms met Clara and Robert Schumann, I was drawn into the world of that 20-year-old with the sensitive face and piercing eyes. His deep regard for them both is palpable, as is theirs for him.

I admire the young Brahms’ support of the Schumanns, especially after the failed suicide attempt, which saw Robert ending his days in an asylum, and I admire how he was there for Clara and her children.

I understand, too, Brahms’ idealism, how he could fall in love with Clara, this talented genius, fourteen years his senior.

It is frequently assumed that he was the one who finally broke free of any romantic attachment. After all, this is the man who later lived according to the tenet ‘free but lonely’.

But perhaps Brahms was always a dear friend as far as Clara was concerned, nothing more. Perhaps pursuing her art to support her children was Clara’s all-consuming passion after Robert’s death. Perhaps she no longer wanted the constraints of a 19th century husband. I don’t know; I need to read more, and even then, I will never know for sure.

For all that is written about the older Brahms and his caustic character, it is the idealist in him which remains with me, and it his enduring friendship with a woman I have come to deeply admire which fuels my imagination.

The sentiments of the following passage from a letter, which Brahms wrote to Clara on Easter Monday, 1872, resonate so entirely:

‘My beloved Clara,

I always spend festivals by myself, quietly in my room, with a few dear ones, as my family are either dead or far away. How good it does me, then, when I feel with delight how love fills my heart.

I am obviously dependent upon the world outside, the chaos in which we live. I don’t join in the laughter; I don’t join in the lies, but it is as though I can lock the best of myself away, and that only half of me goes forth, dreaming.’